The intersection of Portage Avenue and Main Street is at the heart of the city of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, both literally and figuratively. Over the years, people have gathered at this intersection in the centre of the city to celebrate and to protest.

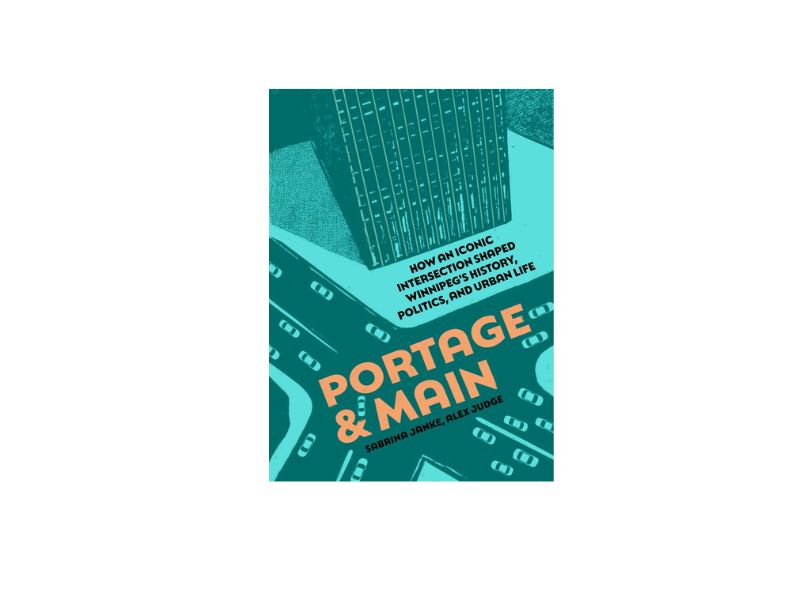

Historians Sabrina Janke and Alex Judge recount the history of this intersection in their book Portage and Main: How an Iconic Intersection Shaped Winnipeg’s History, Politics, and Urban Life, using the intersection as a focal point to show how Winnipeg has evolved. It spans a time frame from the 1860s when Henry McKenney, who is credited with creating the intersection, built a general store at the intersection of two fur-trading routes to the present-day. Although all roads led to McKenney’s store, many considered the location foolish. The land was scrubby and swampy. There was no protection from the strong prairie winds.

The book, published in 2025 by Great Plain Press, is timely. In late June of 2025, the intersection re-opened to pedestrians after being closed to them for forty-six years.

In 1979, the intersection was closed to pedestrians in a forty-year deal the City made with developers as it grappled with what to do about a struggling downtown and increased traffic issues. Pedestrians were redirected through an underground concourse. Janke and Judge write about the events leading to that closure and controversies around them. Some parts of the story were familiar as I had lived through that time. Other pieces were new to me. Together, they presented an overall picture of the time and of the mood of the city.

The re-opening of the intersection was also controversial. In a 2018 non-binding plebiscite, Winnipeggers voted against reopening the intersection, largely because of the cost. But there were still costs required for repairs to the intersection. Then, in 2024, the City estimated many millions of dollars were needed to replace the waterproof membrane protecting the concourse. It became cheaper to open up the intersection.

The stories about the closing and re-opening of the intersection particularly resonated with me. Both had evoked strong feelings in Winnipeggers. At two different points in my life, I had worked in one of the high-rise buildings at the corners of the intersection. When going underground on my lunch breaks, I had often directed some lost soul who had been going round in circles and helped them find the right pathway to their destination corner.

Janke and Judge co-host the podcast One Great History, which presents the great, not-so-great, and just plain bizarre stories of Manitoba history. I encourage you to listen to their podcasts if you haven’t yet. In an easy conversational manner, the two talk about interesting topics in the Winnipeg’s history and explore urban legends and myths.

If you have listened to their podcast, you will know that Janke and Judge spend a lot of time in archives as well as combing through old newspapers and books. The 11 pages of small-print End Notes speak to how meticulously researched the book is. But it does not read like an academic journal. Both Janke and Judge believe in making history accessible. You needn’t be a history nerd to enjoy this book. The authors’ conversational style and penchant for unearthing amusing and quirky bits of history make it very readable.

Stories include one about the university researcher who set out to prove or disprove long-standing claims of Portage and Main being the coldest and windiest corner in the city, the country, or even the world. Another story is about a late 1800s fire in a hotel while people sat in a building across the street watching a slapstick-style farce in which a visitor arrives at a fictional version of that hotel and a variety of calamities occur, including a candle he is given exploding in his hand and the hotel eventually collapsing.

Janke and Judge talked about one of the quirkier stories at their book launch on November 28: a 1920s controversy around creating a cenotaph. A design contest was held for a permanent replacement to a temporary cenotaph erected at Portage and Main by the Women’s Canadian Club. Controversy erupted when the public learned the winner, whose design contained both traditional and non-traditional features, was German-born although he had lived in Canada since he was eight years old. Eventually, the City cancelled his contract. A second winner was chosen a year later. Not only was her design showing a man dressed only in a loin cloth rather daring, it turned out she was the wife of the original winner. Neither version was erected.

These stories do more than amuse. They say something about the Winnipeg of the time. For example, the cenotaph controversy ignited a debate on who was a Canadian. Information Janke and Judge include from newspaper stories, opinion columns, and letters to the editor also help convey the spirit of the city. There were several times as I was reading I thought to myself, “This is sooo Winnipeg!”

Janke and Judge note that current mayor Scott Gillingham has said, “It’s only an intersection” many times. It is only an intersection and yet something about it has captured the hearts of Winnipeggers. Even during the years when it was closed to pedestrians it drew people who came to celebrate, to protest, and to mourn. The gatherings highlighted by the authors say something about what was happening in the city and what mattered to its residents.

The question of what to do with Portage and Main seems to have been a recurring one throughout its history. In the 1860s there were disputes about the exact path and width of Portage Avenue. Figuring out to deal with increased pedestrian and vehicle traffic in the 1930s led to attempts to regulate jaywalking, although one letter to the editor claimed the pedestrian jay-walked to save his life because he is not protected when he crosses at a corner. After the city’s streetcar system was replaced by trolley buses in the 1950s and the concrete safety islands removed, traffic engineers proposed new concepts for the intersection, some practical, some not.

The 2025 reopening to pedestrians has re-ignited discussions about Portage and Main. One is left wondering what the intersection might look like or mean to Winnipeggers fifty years from now.

(Full Disclosure: Yes, Sabrina Janke is a relative. She is my niece. That fact certainly motivated me to buy and read the book as soon as it was released, but it doesn’t change anything I’ve said in the post. I would have enjoyed and recommended the book even if it hadn’t been co-authored by my niece.)

Be First to Comment